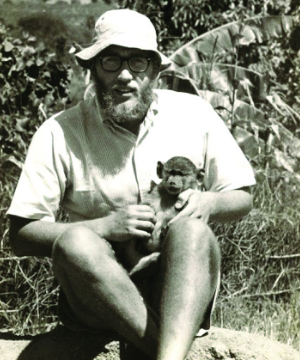

Morgan as a Peace Corps volunteer with baboon Kanini.

An alum reflects

Your Story

Non Ministrari sed Ministrare

“Not to be served, but to serve”

By Russell E. Morgan, Jr. ’65

There I was in 1977, 12 years after graduating from Moravian College, having a conversation with Dr. Halfdan Theodor Mahler, director-general of the World Health Organization, at an early-evening reception in Geneva, Switzerland. Totally unexpectedly, an African delegate came up to us and politely excused himself to say, “Hello, Dr. Morgan, do you remember me? I was one of your high school students in Kenya; I am now a deputy minister of health in Kenya [Hon. Ahmed Halake Fayo]. I just wanted to say hello and thank you as my former teacher.” We continued the conversation for a few minutes, and when he left I said to Dr. Mahler, “If I die tomorrow, life has been worthwhile.”

Growing up in the Lehigh Valley and attending Moravian College, I was exposed to the work of Moravian missionaries serving overseas. I also devoured National Geographic when it showed up at our house every month, and I dreamed of faraway places, particularly Africa, when I read works by Hemingway and others. So it was no surprise when I applied to the Peace Corps, through which I served in Kenya as a secondary education science teacher from 1966 to 1969.

The boarding school where I taught was located in Marsabit, a small town in one of the most isolated parts of northern Kenya—an area that had been closed in the past by the colonial government. The school was one of the first two secondary schools built in the northern frontier districts of Kenya.

Most of my 150 students were from nomadic pastoral tribes: Boran, Rendille, and Gabbra. Others were from Arab, Somali, and Asian communities in local towns where their parents were shopkeepers and businesspeople.

“Hello, Dr. Morgan, do you remember me? I was one of your high school students in Kenya; I am now a deputy minister of health in Kenya [Hon. Ahmed Halake Fayo]. I just wanted to say hello and thank you as my former teacher.”

Living and teaching in Kenya provided exciting opportunities to meet new people and learn about different cultures, which in turn helped me to better understand myself and my values. What impressed me most was the personal determination of all of my students to succeed, despite the tremendous barriers they faced. Education was their one opportunity to move forward in their professional ambitions. So though the school had electricity only until 7:00 p.m., when I would conduct a bed check later in the evening, I would find students huddled under their sheets with a flashlight studying—often despite 90-degree temperatures, no air conditioning, no window screens, and possibly also suffering from dysentery, malaria, or some other disease.

The straight-line geographic boundaries of northern Kenya were drawn in the late 1800s by expatriates—mainly British and Italian—in a way that was calculated to maximize access to political and natural resources. As a result, these borders cut through tribal areas in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia. Thus, our school had students from all of these regions representing a broad range of social, ethnic, and political perspectives. Since the school was physically located in Kenya, however, it was used as a political pawn to keep down tribal rivalry. One of the great challenges I faced was to teach science in English so the students from these different backgrounds could pass the British Cambridge Exam, while at the same time helping them preserve their cultural identity. (The Kenya Ministry of Education soon after developed its own matriculation exam to replace the Cambridge Exam.)

Mohamud Said, MD (second from left), accepts the Harris Wofford

Global Citizen Award. With him (left to right) are Peace Corps Association

President Glenn Blumhorst, Russell Morgan, and former Senator

Harris Wofford. Photo credit: National Peace Corps Association

I returned to the United States in late 1969 to pursue my own life goals, just after the senior class completed its Cambridge Exams, but those three years in Kenya forever cemented my connection with my students and their dreams. I am thrilled by the unbelievable success of this class. They have gone on to highly responsible positions, including Kenyan Ambassador in Beijing, international lawyer, member of parliament, educational attaché of the Kenya High Commission in London, and assistant commissioner of police. One lives in Maryland and is a renowned orthopedic surgeon, and the daughter of another is a lawyer and has established the nonprofit organization Horn of Africa Initiative (HODI) to help improve people’s lives in Marsabit.

I am privileged to have a particularly close relationship with one former student—Mohamud Said, MD. After attending college in Kenya, he received his medical training in Russia and returned to Kenya to set up a private practice clinic. He pursued international training in human rights and medical legal issues and has been appointed to the Kenya National Committee on International Humanitarian Law. As a surgeon, Dr. Said has done considerable work in reconstructive surgery in crisis areas around the world, especially collaborating with medical specialists from Spain. He has served as president of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims, based in Copenhagen, and has received international awards for his leadership in international human rights. Currently, he serves as the chair of HODI and the governor (president) of the Kenya Red Cross Society, which oversees one of the world’s largest refugee camps in Daadab, a town in northeastern Kenya.

In 2013, Dr. Said was presented with the National Peace Corps Association Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award at Harvard University for his outstanding service and for modeling his life after many of the values embedded in the Peace Corps philosophy. It was a very proud moment for both of us.

My experience of Africa, its people and cultures, inspired my career in global public health policy and politics. For the past 50 years, I have traveled around the world and worked with people of many ethnicities. I have encountered new perspectives on culture, policy, and social justice, and I have shared my culture and views. Collectively, I hope these experiences have made me less biased in a world that at times seems to have no tolerance for differences.

Through my global experience, I hope I have become a better contributor to the global community. I have learned to listen carefully to the views of others; tried not to be biased and jump to conclusions without first understanding the source and possible cultural implications; and always been willing to correct my views if I discover I misunderstood or misinterpreted a message. And I hope that what I’ve learned, I’ve passed on to others through my example.