An alum reflects

Your Story

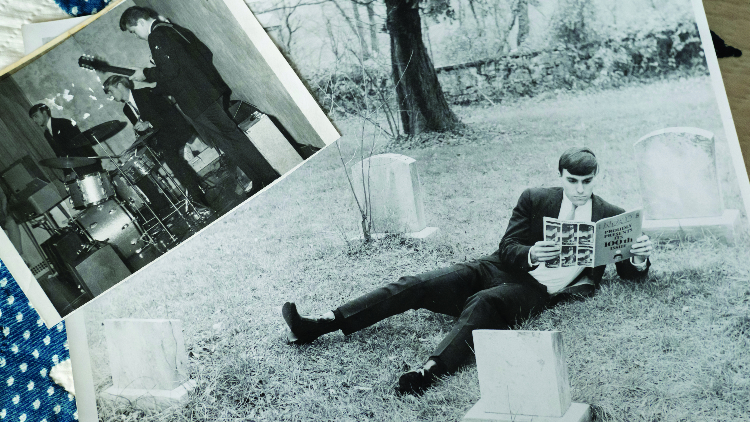

’60s Rock Star

By Jerry Clymer '69 as told by Anna Villegas '18

Photographs by Theo Anderson

I was still in high school when I joined the band. We were called Joey D. and the Four Kings. They were friends of mine, and I kind of weaseled into the group. I dabbled with the piano and I played the guitar, and it was a fit—a perfect fit. I mostly played the keys, and every once in a while a song on the guitar, but I was rhythm. I did all the rhythm.

We must have sounded pretty good, because a disc jockey on WEEX, Jay Edwards, came to us and said, “I’m gonna get you to cut a record.” We shrugged him off, but he said, “You’re going to sign with Roulette.” Roulette was big time, so we signed the contract. They wanted us to change the band’s name. We resisted, but it was either change the name or no record. They decided to call us The Morticians. “What kind of a name is that?” we asked. They said, “You don’t look like morticians, so it’ll stick. People will remember that, and they’ll remember who you are.” So we became The Morticians. We dressed in black suits. And we cut the single “Now That You’ve Left Me.”

We started to make some money, and we bought a huge truck. Every weekend, we’d play at the fraternity parties at Lehigh, Lafayette, and Penn. The truck was in such bad shape that one time at Lehigh, we had to get out and push it up the hill. We had some tough times. We only made so much. But, as kids, we didn’t care; we were having a ball.

We played concerts everywhere. We played at the Alibi Lounge in Atlantic City, and it was packed all the time. But while it was fun, I was also struggling with playing every weekend, practicing during the week, and having to do school. I’d say to my mom, “Hey, this is tough!” She’d say, “Well, live with it.” I did. It was either that or quit the band, and I wasn’t about to do that. I understood that education was important, and that my mom was not about to relent.

At some point, there was talk of the band going to Europe, but my mom wouldn’t hear of it. “He’s staying in school! He’s not going anywhere!” she said. We were having fun, so we weren’t too heartbroken by not being able to go. But because we didn’t go to Europe, Roulette started to pull back from us—and their other group, Tommy James and the Shondells, started to wipe us clean. They went on to have a number-one record with “Hanky Panky.” Our single was moving up the charts, but it was moving much more slowly.

Still, we were very popular at the Alibi Lounge. We heard a rumor that George Harrison had listened to our single, liked it, and taken it to England, and that he and Brian Epstein were coming to the Alibi to watch us perform. That particular night we were feeling run-down from the constancy of performing, and we decided to ask for more money. When we were told no, we threw all our gear into the truck and headed back to Phillipsburg.

When we pulled out of the Alibi Lounge, we panicked because we knew we hadn’t fulfilled our contract with Roulette. We were kids, but we still owed somebody something. We owed the wrong or right people, and we were scared to death. Thankfully, we got a reprieve. We don’t know who gave us a reprieve, but we were left alone. We could carry the name The Morticians, and we could take the Roulette recording with us, but we were on our own. It wasn’t until after the fact, when the full story of Roulette’s mob connections became public knowledge, that we fully understood what we had gotten into and, luckily, out of.

“A while ago, a lady came up to me and said, “I know you; you’re a rock star.” I said, “Nah, I’m not.” But she insisted. I’ve got your record,” she said.

When I think back, if we had fulfilled all the requirements of our contract with Roulette, it might have been Europe, the big time, and maybe millions of dollars. The Beatles were at the top at the time, and we were told that Roulette thought we were going to compete with them. We signed the contract with Roulette in ’66, and our band broke up in ’69. I don’t remember who left the band first. We all went our separate ways. Some of the guys joined other bands, but they didn’t stick. I had opportunities to join other bands, but it wasn’t the same. The work ethic wasn’t the same.

I went into school administration and eventually became superintendent of the Andover Regional School District in New Jersey. When I retired, my son’s band played “Now That You’ve Left Me.” With the new technology, their sound was so good that I started thinking about getting the band back together to redo the song. I called up Barrie Wright, The Morticians’ drummer, and he came to the house. That’s when I found out that Jim Olexa, our guitarist, had passed away. Joe Dudish, our lead singer, was up in Boston somewhere, and I couldn’t find our bassist. Then there’s just me.

In 2000, I was told that I had Parkinson’s disease and there was no cure. I disagreed 100 percent with the doctor and said I was going to beat it. When I got home, I went right downstairs to the studio my son built, and, even though I hadn’t touched a guitar in years, I grabbed his guitar and started playing. And I haven’t stopped. My left side used to be my weaker side, but it’s my stronger side now.

I play the guitar for about 3 hours every day. I figure, “I’m gonna beat this.” I’m still like a kid; I turn the amps up real loud. I probably drive the neighbors nuts. But it’s relaxing. Believe it or not, I play better than I did 20 years ago. I mean, I could pick up with a band right now and go, but I don’t want to do that. I’m 71, but I’d blow your socks off. Give me an amplifier and a guitar and I’ll go nuts.

Writer Anna Villegas graduated from Moravian College on May 12, 2018, with a bachelor’s degree in media and culture.