Advancing Covid Testing

As COVID-19 grew into a global pandemic, the demand for testing skyrocketed. At Roche Diagnostics, principal scientist Andrew Cohen ’10 played an integral role in the rapid delivery of a diagnostic test, authorized for use in March.

By Claire Kowalchik

Andrew Cohen builds bridges. Not the ones you drive across but the science-based technical bridges that drive the production of tests used to diagnose disease. Cohen is a principal scientist in Design Transfer and Technical Support, Global Operations, at Roche Diagnostics in Branchburg, New Jersey. When the research and development team at Roche designs a diagnostic test, Cohen builds the processes to transfer the design to the operations team, and he supports that team in developing and manufacturing the test on a large scale.

In March of this year, he was pulled onto an emergency response team assigned to develop a test for SARS-CoV-2. “I was part of a cross-functional team—research, development, operations—tasked with developing the assay for high-volume testing in a matter of weeks,” says Cohen. “The normal process time for a new test can range from 12 to 18 months, even longer.”

A PCR Primer

Roche diagnostic testing employs polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect and replicate nucleic acid for scientific analysis. Considered one of the most important advances in molecular biology, PCR revolutionized the study of nucleic acid, and in 1993, its inventor, American biochemist Kary B. Mullis, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Think back to your biology classes. Nucleic acid is the genetic code that defines each individual animal, plant, bacterium, and virus. One way to find out if you are infected with a virus is to search for that virus’s nucleic acid in a sample of blood or saliva or, as we’ve seen with COVID-19 tests, on a swab from the upper respiratory tract. Of course, one never knows how many nucleic acid molecules are present in that sample, and the amount could be very small—just a handful, in fact. So to perform molecular and genetic analysis requires significant amounts of nucleic acid.

That’s where PCR comes into play. The process targets a specific segment of nucleic acid in a sample and amplifies the amount by replicating it.

Let’s take SARS-CoV-2 as an example. First, RNA is extracted from the patient sample. It is mixed with a cocktail of reagents (manmade chemicals) designed to bind to any SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the sample and copy it many times over: One set of reagents, called primers, will bond only with the SARS-CoV-2 RNA segment if it is present, and another set of chemicals then replicates that segment. Throughout this process, the temperature of the sample is raised or lowered to facilitate the desired chemical reactions. After a predefined number of these PCR cycles, more than one billion copies of the original DNA segment have been made. (For a more thorough but still accessible explanation of PCR, visit mrvn.co/pcr.)

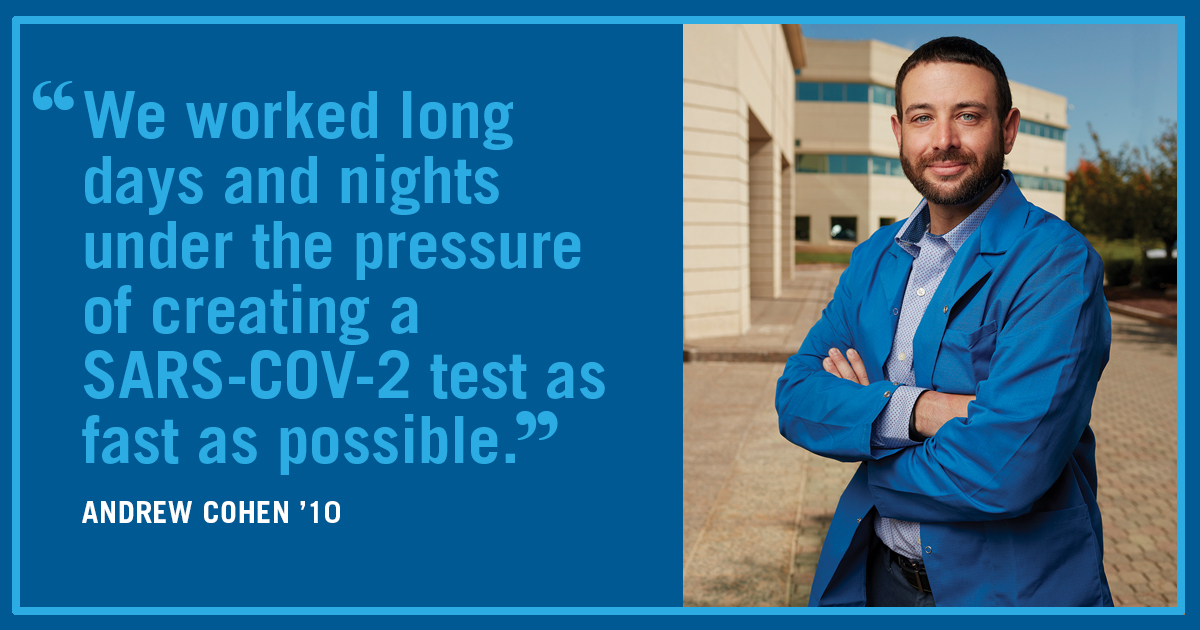

“We worked long days and nights under the pressure of creating a SARS-CoV-2 test as fast as possible.” —Andrew Cohen ’10

Andrew Cohen at work in the lab

The Life Cycle of a Diagnostic Test

At Roche Diagnostics, the research and development team designs the PCR diagnostic test (also called an assay) specific to a pathogen (e.g., SARS-CoV-2). Working from genetic sequence, they determine the cocktail of reagents and other materials needed to test for and replicate that nucleic acid. Next, the individual reagents are produced and combined with additional materials to make full diagnostic kits. Those kits are manufactured on a large scale and sold to laboratories and hospitals around the world that then perform the PCR diagnostic test on patient samples.

The tests are run on Roche’s fully automated high-throughput Cobas 6800 and Cobas 8800 instruments, providing up to 96 results in about 3 hours and 384 results for the Cobas 6800 System and 1,065 results for the Cobas 8800 System in an 8-hour shift.

The Master Link

Cohen creates the processes for transfer of the work done in research and development to operations and then onto large-scale manufacturing of high-quality test kits. “Our team provides creative solutions and services to ensure exceptional transfer of new products into operations and to support molecular diagnostic test quality throughout the production lifecycle,” explains Cohen. “I am the lead representative for anything that comes through our high-throughput Cobas 6800 and Cobas 8800 instruments.” Roche Diagnostics develops and manufactures tests for a wide range of infectious diseases, including HIV, hepatitis, Zika, and West Nile virus.

If it all sounds very technical and complicated, it is.

Cohen gets it—all of it.

A 2010 graduate of Moravian with a B.S. in chemistry, he accepted a position with Roche Diagnostics in June, just a month after graduating. “I’ve always loved science. When I came to Moravian, I knew I wanted to do something in chemistry or physics or engineering. I didn’t know I would go into the diagnostics industry,” says Cohen. “At Roche, I started in manufacturing and worked there five years before moving into my current position.”

While at Roche, Cohen also earned a master’s degree in materials chemistry from the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he focused on inorganic and polymeric analytical methods, spectroscopy, and synthesis. In June 2018, he earned a certificate in applied project management from Villanova University. “I love what I do,” he says. “It involves project work and travel, and I collaborate with fantastic people in teams all over the globe.”

Answering the emergency call to develop and deliver a COVID-19 diagnostic test this past spring required Cohen to bring all of his skills and scientific knowledge to the work and give his best performance day after day. “We worked long days and nights under the pressure of creating a SARS-CoV-2 test as fast as possible,” he says. “But it felt so good to contribute directly to something that helps save lives. Delivering on that goal was a really proud moment for everyone.”

Three scientists from the Class of 2017 (left to right):

Jennifer Degnan, Raymond Morales, and Amanda Miller.

A Moravian Trio at Roche

Jennifer Degnan, Amanda Miller, and Raymond Morales graduated from Moravian College in 2017 and that same year were hired by Roche Diagnostics in Branchburg, New Jersey, to work on various aspects of Roche’s polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for diagnosing disease.

Jennifer Degnan grew up in Nutley, New Jersey, only a mile from the former Roche site, never imagining she might someday work for this giant in the medical diagnostic industry. At Moravian, she earned a B.S. in biology and a certificate in secondary education with the intent of becoming a high school science teacher.

During her undergraduate years, she completed a SOAR (Student Opportunities for Academic Research) project in stream ecology and attended the University of Massachusetts in Boston for an REU (Research Experiences for Undergraduates) in marine biology and ecology. “I liked ecology but wanted to pursue research that gave me more time in the lab,” says Degnan, so in her senior year, she chose to do an honors project in genetics with biology professor Christopher Jones.

In June 2017, Roche Diagnostics offered Degnan a job in its Manufacturing Critical Materials Department, Global Operations, where Degnan made oligonucleotides that are used in the company’s PCR-based diagnostic kits. “I then moved into a more biology-related role manufacturing enzymes and control stocks that are also used in diagnostic tests,” she adds.

In the summer of 2019, Degnan joined a research and development group focusing on the development of an innovative class of molecular tests that quickly identify multidrug resistant organisms (MDROs) like MRSA and CRE.

“Our work has positively affected people all over the world, and I am very proud to be a part of it.” —Amanda Miller ’17

Then COVID-19 hit.

Degnan moved into her previous group to assist with the manufacture of oligonucleotides because the demand skyrocketed in the race to produce diagnostic tests for SARS- CoV-2. “The work we do at Roche is rewarding, uplifting,” says Degnan. “We are really having an impact.”

Amanda Miller agrees: “Our work has positively affected people all over the world, and I am very proud to be a part of it.”

A native of Nazareth, Pennsylvania, Miller earned a double major in biochemistry and management with a concentration in organizational leadership. She began her career with Roche in December 2017. In her Global Operations role, she purifies enzymes that are used in PCR diagnostic tests. “I am also currently involved in validating new equipment for use in the manufacturing process of our tests,” says Miller.

Degnan, Miller, and Morales continue to work on SARS-CoV-2 testing as well as Roche’s full portfolio of tests for blood screening, infectious diseases, and other life-threatening conditions.