The Book Collector

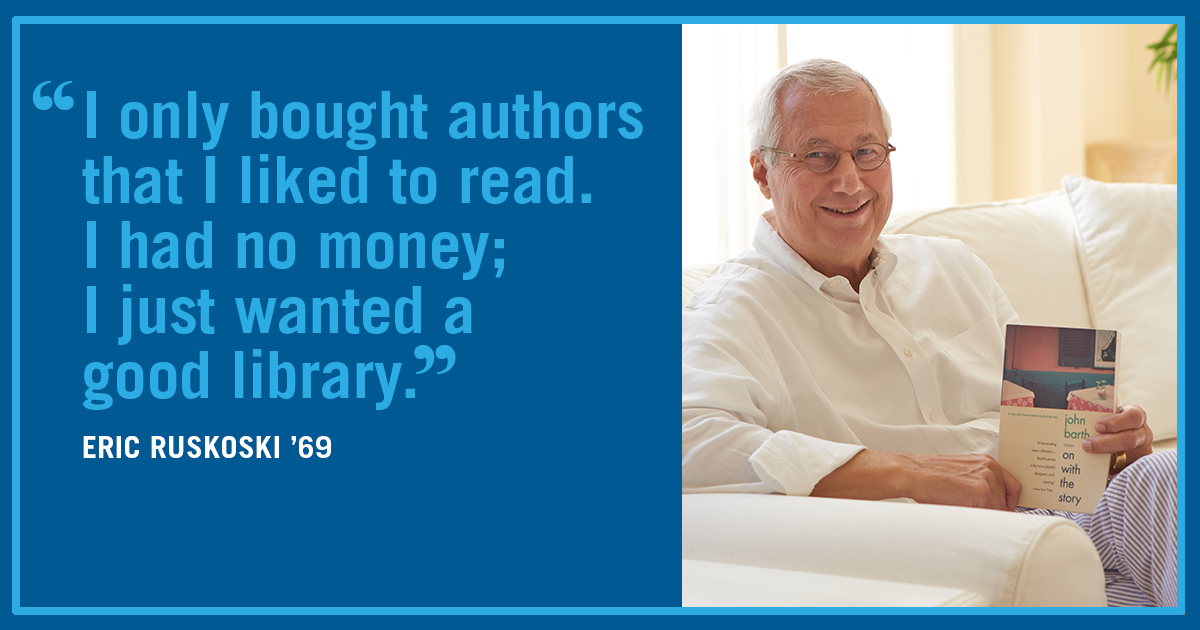

For Eric Ruskoski ’69, the pursuit of a career had many unpredictable changes in direction, eventually leading him to become one of the founding entrepreneurs of a very successful business, but his love of literature was a constant. Over the years, this voracious reader acquired a considerable collection of books, including rare and first-edition volumes, many of which he recently donated to Moravian College.

By Anndee Hochman

Photographs by Monica Buck

He wasn’t supposed to be reading Moby-Dick.

But in Eric Ruskoski’s sophomore high school English class—which he wryly refers to as the “dumbbell class”— most students weren’t reading anything at all. So when the teacher strolled by Ruskoski’s desk and saw the fat volume with the whale on the cover, he was intrigued. “Stand up and give a book report,” he said. “Just talk about it.”

“So, with nothing prepared, I talked about it,” Ruskoski recalls. “I gave seven hourlong classes on Moby-Dick.” At the end of the term, the teacher promoted him to honors English. “It’s sort of the story of my life,” Ruskoski says—a series of false starts and intuitive leaps leading to unpredictable achievement and success.

It was a path that in 1976 led him to start what became the leading global manufacturer of dispensing closures for packaging—such as the innovative flip-top and upside-down dispenser caps now ubiquitous on ketchup, honey, and other products—and to become a collector of rare, first-edition books, mostly by modern American authors. Ruskoski recently donated part of his collection to the college. It includes a first edition of Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms along with numerous books by John Updike, John Dos Passos, and John Barth.

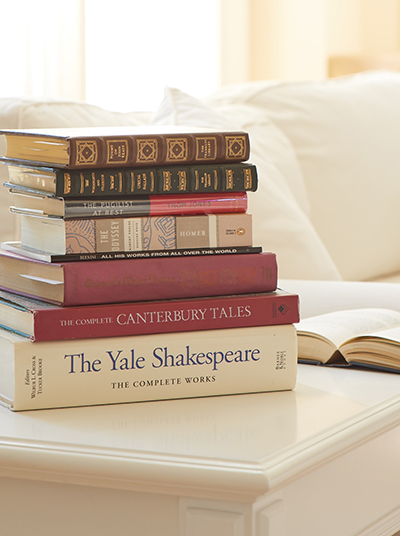

Poems of John Keats: “From my class on 19th century poetry.”

Wordsworth and Coleridge: “I’ve been reading and rereading this since Dr. Burcaw’s class.”

The Pugilist at Rest, by Thom Jones:

“I reread this recently along with Jones’s Sonny Liston Was a Friend of Mine.”

The Odyssey, by Homer: “I reread it last year.”

Bernini: All His Works from All Over the World, by Andrea Zanelli: “A gift from my daughter from when she was studying abroad in Paris. My wife, Sandy, was hiking in Cinque Terre, and I was working in Bavaria, so we met in Rome and went to Villa Borghese to see some of this sculptor’s greatest works."

Chaucer’s Major Poetry, by Albert C. Baugh: “In Middle English, from my years in graduate school at the University of Maine.”

The Canterbury Tales, by Geoffrey Chaucer: “A retirement gift from my management team in England.”

The Yale Shakespeare: “A gift and good reference book but too cumbersome to read. Since Doc Burcaw’s class, I’ve regularly read Shakespeare and listened to lectures.

I visited London frequently enough to get to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre a few times a year, and I support the Chicago Shakespeare Theater.”

Ruskoski entered Moravian thinking he would become a doctor, an ambition that crashed after he failed trigonometry (twice), floundered in organic chemistry, and fortunately realized, as chemistry professor Morris Bader pointed out, that he was more interested in playing football than in becoming a doctor.

He’d always loved literature—the Moby-Dick he’d picked up in the drugstore where he worked as a teenager in Hillside, New Jersey; J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye; books about Darwin and the Galapagos Islands.

English professor Robert Burcaw enabled Ruskoski to switch his major to literature after he promised he would do his best to be a devoted student. In Moravian’s first Jan Plan, English professor George Diamond introduced Ruskoski to the work of John Barth and Bruce Jay Friedman, novelists known for their dark humor and postmodern sensibilities. He became interested in authors’ lives as well as their works. And he credits Moravian professors, including Burcaw, Diamond, and Bessie Michael, for encouraging him in spite of his erratic performance as a student. “Even when it appeared that I didn’t have an interest in my own education, the professors at Moravian took an interest, inspiring me to press on,” he says.

“Getting on the right track took me from probation to Dean’s List,” he notes. Graduate school at the University of Maine became another mind-shaping development. Ruskoski enrolled there thinking he would become a professor or a writer, but he could see from conversations with classmates (including Stephen King, who by then had declared himself a writer) that he was unlikely to succeed in the worlds of professional writing or academe. Ruskoski began a master’s thesis on Barth but never completed it.

Instead, he decamped for six months of backpacking around Europe, then returned to a string of jobs—bartender, freight railroad brakeman, truck driver, furniture loader—in the United States. In his spare time, he browsed used bookstores.

“When I got to Paris, I found a Philip Roth book, Goodbye, Columbus, and I just started reading it. Roth grew up in a town next to where I grew up, so it was kind of a connection.” He began to pick up first editions of books by authors he loved: Salinger, Updike, Saul Bellow. Hemingway. Fitzgerald.

“I only bought authors that I liked to read,” he says. “I had no money; I just wanted a good library.” Once, at the Strand Book Store in New York, he rejected a hardcover copy of the short story collection Lost in the Funhouse, by Barth, because he thought it was too expensive at $22. “It wasn’t a mission of mine to become a book collector, but somehow it became part of what I was doing.”

photographs by Luke Wynne

photographs by Luke Wynne

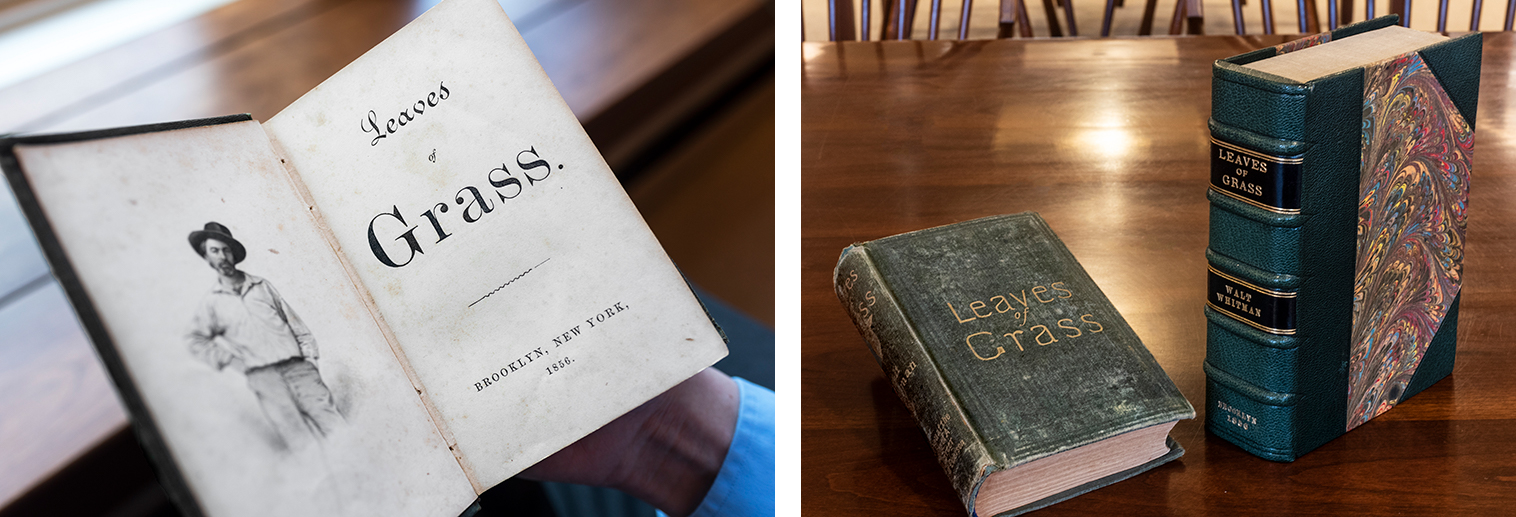

Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass

The prize among the books that Eric Ruskoski has donated to Moravian College is a first octavo edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. (Octavo refers to the process of printing 16 pages, or eight leaves, at a time on a large sheet of paper that is then folded three times and cut.) This edition, published in 1856, a year after the first edition, was printed for the Whitman family. Rare book experts believe the book belonged to Whitman’s sister, Mary Elizabeth, who passed it on to her daughter and finally to her granddaughter Zora Tuthill, whose inscription appears in the front.

For this edition of Leaves of Grass, Whitman added 20 poems to the original 12, a letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson praising the book along with Whitman’s reply, and several reviews. With subsequent printings, Whitman continued to revise the work and to add poems up until his death in 1892. According to the Walt Whitman Archive, the final and ninth edition, printed in 1892, contains 293 poems.

Leaves of Grass is a monumental work not only for its depth and breadth but in its revolutionary themes and poetics. Inspired by his travels across the country, Whitman overthrows the traditions of British verse and creates a uniquely American voice that breaks with the conventions of rhyme, meter, and elevated language and replaces it with a prosaic verse echoing the cadences and phrasings of Biblical texts.

In theme, Leaves of Grass celebrates democracy, nature, friendship, love, sexuality, the divine in human body and soul. Whitman proclaimed a connection between the individual and America’s democracy. As the editors of the Walt Whitman Archive (whitmanarchive.org) write, “It was Whitman who was the most radical in avowing that American identity was inextricable from the nation’s central premise of self-governance and equality. In poems such as ‘Song of Myself,’ he stressed to his readers how their individual lives constituted the very circumference of democracy. ‘[T]he genius of the United States,’ he pronounced, ‘is . . . in the common people.’ ” And Whitman’s conviction in egalitarianism and the unity of all people is expressed succinctly in the very first lines of Leaves of Grass:

“I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

—Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself ” (1892 version)

Sources: poetryfoundation.org, poets.org, whitmanarchive.org

In the meantime, his book collection outgrew the space in his parents’ Pennsylvania barn, where he initially stashed the volumes, eventually filling custom-made shelves and credenzas in the home he and his wife, Sandy, built in Chicago.

If Ruskoski loved a particular author, he tried to acquire everything that person wrote. He browsed secondhand book shops in New York, Boston, and Chicago and on trips abroad. He attended readings and asked authors to sign their books, which made them more valuable.

The turning point from hobbyist to serious collector came when Ruskoski acquired a second edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass printed in 1856 (a year after the original) for Whitman and containing 20 additional poems. Whitman gave it to his sister, Mary Elizabeth, who then passed it to her daughter, Zora Tuthill, whose inscription appears in the front.

Ruskoski’s collection became a panoply of 20th-century modernist authors—Tim O’Brien, Ethan Canin, Thom Jones, and Larry McMurtry, along with Dos Passos and Hemingway. A few acquisitions strayed from that category; his collection included Shakespeare, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Camus. Ruskoski didn’t just acquire the books; he read, and often reread, all of them.

“McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, I could read a hundred times, probably. And Updike, I think he’s the best writer of our time.” When he read Jones’s The Pugilist at Rest, he was inspired to visit the statue that prompted the book’s title—a Hellenistic Greek sculpture housed in a tiny museum in Rome. “The book is about a guy who was a boxer in the Marines,” Ruskoski says. “But I’d go sit by the statue, and it struck me: This has more dimension than just a story.”

photograph by Luke Wynne

photograph by Luke Wynne

“[T]hat which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson, “Ulysses”

“What Tennyson had to say kept me going. Those last four lines, about striving and reaching for the stars.” —Eric Ruskoski

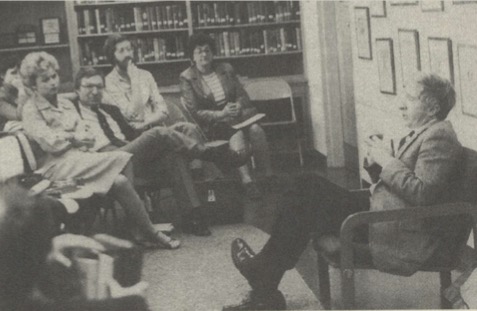

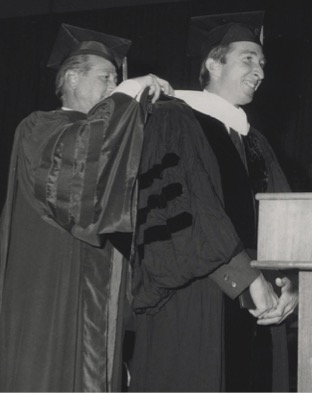

John Updike revisited Moravian College on March 12, 1982.

He read excerpts from some of his books and then was interviewed by

English professor George Diamond. On the occasion of that visit,

a tree outside Colonial Hall was dedicated to Updike.

John Updike

John Updike may be best recognized as the author of the Rabbit series of novels—Rabbit Run, Rabbit Redux, Rabbit Is Rich, and Rabbit at Rest—and the novella Rabbit Remembered, but he also wrote short stories, poetry, essays, and criticism. The prolific writer published 60 books in his lifetime, and of those 60 books, Eric Ruskoski ’69 donated 44 titles, most first editions, to Moravian College last year.

“My subject is the American Protestant small-town middle class,” said Updike in a 1966 interview for Life magazine. “I like middles. It is in middles that extremes clash, where ambiguity restlessly rules.”

John Updike received an honorary Doctor of

Humanities degree from Moravian College on

October 19, 1967, as part of a program marking

the dedication of Reeves Library.

Updike was born on March 18, 1932, in Shillington, Pennsylvania, just outside of Reading, and much of his early work is set in Pennsylvania middle-class towns reminiscent of Shillington. His father was a high school teacher and his mother an aspiring writer. Updike received a full scholarship to Harvard, where he majored in English, and graduated summa cum laude in 1954. In 1955, he began writing for the New Yorker, and from there, his career rocketed. He is one of only four novelists to win two Pulitzer Prizes: in 1982 for Rabbit Is Rich and in 1991 for Rabbit at Rest. Updike was also twice awarded the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award and is among a select few to receive both the National Humanities Medal and the National Medal of Arts.

Moravian College holds the distinction of being the first educational institution to offer a John Updike course, which was developed by Lloyd Burkhart, then professor of English and department chair, in 1970.

John Updike died January 27, 2009, in Danvers, Massachusetts.

“I seem most instinctively to believe in the human value of creative writing, whether in the form of verse or fiction, as a mode of truth-telling, self-expression and homage to the twin miracles of creation and consciousness.”

—John Updike, from his essay “This I Believe”

In His Own Voice

You can listen to a recording from Updike’s 1982 visit to Moravian College at mrvn.co/updikevisit.

While Ruskoski occasionally uses an electronic reader, mostly for reading at night and when he travels, he prefers the real thing. “I’m one of those tactile people; I like to have something in my hands.” Actual books offer texture—the dust jacket, the deckled pages—that a digital book does not, along with the flexibility to leaf forward and backward easily.

“First state” editions (the earliest run of a first edition) fascinate him with the errors that show the imperfect path of a manuscript from the author’s mind to final publication. “There might be a woman’s name spelled incorrectly on the back flap, or the name of a train station is incorrect, or letters left out—that gives some sense of how this thing got from the author’s brain and what happened to it as it was getting into print.”

Ruskoski credits books for expanding his frame of reference. “At Moravian, and through reading literature, I got a much broader view of the world than most people. I’m very, very grateful for having had those opportunities, even though I didn’t appreciate them at the time,” he says.

Now, as a retired entrepreneur who has traveled the globe and who divides his time between homes in the United States and St. Lucia, he’s drawn to local authors—Carl Hiaasen, a journalist and novelist who writes about South Florida, is a new favorite—and enduring classics such as Homer’s Odyssey.

When he was working toward retirement—it took 2½ years to create and execute a plan for transition—he had the habit of reading the poem “Ulysses” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, nearly every Saturday morning. The poem ends with an encouraging message:

“[T]hat which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

“What Tennyson had to say kept me going,” says Ruskoski. “Those last four lines, about striving and reaching for the stars.”

Anndee Hochman is a journalist, essayist, and storyteller. Her column, “The Parent Trip,” appears weekly in the Philadelphia Inquirer,

and her work has also been published in Poets & Writers, Broad Street Review, Purple Clover, and other print and online venues. She is the author of Anatomies: A Novella and Stories as well as an essay collection, Everyday Acts & Small Subversions: Women Reinventing Family, Community and Home.

Six of Ruskoski’s Top Picks

Asking Eric Ruskoski ’69 to cite his favorite books is a bit like asking a parent to name her best-loved child. Still, there are volumes he returns to, rereading them periodically and finding new insights and pleasures in their pages.

When choosing a book, he says, he’s often drawn in (or turned off) by the first few sentences. “I’m a big believer in what your gut tells you in the first 90 seconds of something. Instinct. Intuition. Gut feel: What does this guy have to say?”

Here are a few of Ruskoski’s top picks, along with the first line of each book and his impression of it.

Catch-22

by Joseph Heller

“It was love at first sight.”

“I read it as an undergrad; someone had the book and said it was really great. I read it within a day. What struck me about it was the macabre humor; it was in that era of black humor, apocalyptic humor. The bizarreness of being at war. Heller came to speak at the University of Maine; it was interesting to learn about the pain and suffering he went through on publication of his first book.”

Lonesome Dove

by Larry McMurtry

“When Augustus came out on the porch the blue pigs were eating a rattlesnake—not a very big one.”

“Which books do I go back and reread? Lonesome Dove, I could read a hundred times—for the characters and the odyssey that they take. I talked to McMurtry on the telephone a couple of times. He was a bookseller, kind of a curmudgeon.”

Lost in the Funhouse

by John Barth

“For whom is the funhouse fun?”

“In a class on black humor, we read Barth and Bruce Jay Friedman, a book a day, and I wanted to know more about these authors. I went to quite a few of Barth’s readings in Chicago, enough that I could actually have a conversation with him. I had written my master’s thesis on him. I didn’t tell him I’d never actually finalized it.”

Moby-Dick

by Herman Melville

“Call me Ishmael.”

“I worked as a soda jerk in a drugstore during high school. They sold books. I had no customers one night, so I was looking at the bookshelf and saw a paperback copy of Moby-Dick, with the big whale and the ship getting smashed, and it looked like a worthwhile read. I’ve read Moby-Dick probably four or five times.”

The Centaur

by John Updike

“Caldwell turned and as he turned his ankle received an arrow.”

“I think he’s the best writer of our times. He’s so prolific, and everything he writes is a work of art, really. I met him when I used to go skiing in New Hampshire. I was a failure at writing, so it was a little bit intimidating. We stood around in the ski shop, chatting. I said, ‘We just read one of your books at Moravian.’ ”

The Catcher in the Rye

by J.D. Salinger

“If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.”

“Catcher in the Rye was all the rage when I was in high school. I would read during study hall, outside of the course work. Later, I got to know about Salinger, that he was a recluse. I knew I’d probably never get to meet him.”

Learning with the Ruskoski Collection

The collection of 150 first-edition books donated by Eric Ruskoski fills nearly seven long shelves in the Special Collections and Rare Books Room, which is on the first floor of Reeves Library. The Rare Books Room is locked, and only a few members of the library staff have the key. But rest assured those volumes will not be left in the dark.

Cory Dieterly, Moravian’s archivist and one of the holders of the key, has big plans. He has developed a richly educational paid internship for students interested in a career in education, preferably those who wish to teach English. The work involves creating a series of exhibits in Reeves Library and online that showcase rare books and their authors alongside any archival materials that reveal a connection between the authors and the college. The first exhibit will showcase the works of Walt Whitman, highlighting his epic work Leaves of Grass. A rare edition printed in 1856 is part of the Ruskoski collection. The Whitman exhibit will be followed by one describing John Updike, his work, and his visits to Moravian. Subsequent displays will be of the student’s choice.

The internship will provide students several academic and professional experiences as outlined in Dieterly’s proposal:

- Stimulate critical thinking and develop writing skills through research with primary source materials.

- Learn to identify reliable secondary sources for historic and literary research.

- Cultivate critical thinking skills and imagination by creating curriculum using those source materials.

- Acquire in-depth knowledge relating to contemporary literary authors through the study of unique historic primary source materials and early drafts of famous literary works.

- Gain hands-on experience developing curriculum for college-age students.

- Acquire experience with performing independent research and writing curriculum.

- Exercise standards and best practices for handling and exhibiting archival materials for preservation and public display.

- Publish a web page to exhibit digitized and curricular materials, which can be included in the intern’s graduate school and/or job application portfolios.

To learn more about the internship or the college’s collection of rare books, contact Cory Dieterly at DieterlyC@moravian.edu.